Meryl Thomas Palakunnel

American women and WWII

Repositioning of women from being producers to consumers in the post World War II period through advertising in the United States of America

This paper takes a closer look on the liberation of women from their domestic households when women were offered jobs at offices and factories during the Second World War, and later were encouraged to go back to homemaking or rather persuaded to go back to ‘confinement’ after the war. This was done through extensive advertising portraying women in an unrealistic manner. Advertising played a central role in both, persuading women to take up jobs at the war industry production factories and later in encouraging them to take up ‘home-making’ as an important ‘job’. The role of advertising in both the aforementioned aspects aimed at white middle-class women of America shall be discussed in this paper.

The gender role ideology that prevailed in America was that of separate spheres, public and private where in which the public sphere was regarded as masculine and the private sphere was regarded as feminine[1]. Women were confined to household work and domesticity whereas the men were the breadwinners of the family. With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, a significant breakthrough took place in ‘a woman’s conventional role’ in the United States of America. It was a time when ‘gender conventions’ took a non-traditional turn. The image of a woman in the United States was that of a confined one whose sole purpose was child-bearing and homemaking. Betty Friedan in her book, The Feminine Mystique, draws a parallel between the image of women in Nazi Germany and The United States of America where the traditional role of a woman is being a mother and wife[2].

Several articles were published in newspapers and magazines to promote or rather perpetuate the existing norms of ‘an ideal woman’, glorifying a woman's role as a mother and wife[3]. Renowned American women writers such as Abbott, Cook, Lane and Thompson advised women to devote themselves and their talent in looking after their families rather than work outside of their homes, hence reinforcing the image of an American woman as an educated and skilled homemaker[4].

With the men heading off to war, the labour force at various ‘male-dominated’ industries such as the ammunition factories, were plummeting. The government realised that the largest available source of labour in the country are the women of the country and called out to them to pick up tools and get to work to support the war effort which was an unusual scenario since in the 1930s during the Great Depression women were discouraged from working outside their homes and were told they had no rights to take a job from a man who is working hard to support his family[5]. The women of America were under tremendous pressure to hold on to ‘traditional homemaking’ whilst undertaking jobs that were initially labelled as ‘only for men’. However, this change was not welcomed by many employers, ‘the men’ in the society and some women as well, since they found breaking away from a woman’s traditional role seemed preposterous, the pressure to carry on a ‘traditional home’, and even if they were ready to work, the fear that their family life may fall apart held them back. Social constructs such as a ‘traditional housewife’ and even racism were put aside to meet the labour shortage in the war industry. Emily Yellin quotes a line from President Roosevelt’s speech on Columbus Day in 1942, where he said that they could no longer afford prejudices such as hiring women or the coloured[6]. However, the belief that this change, women taking over ‘men’s jobs’, is short-term until the men returned home from the war was a cue to set things in motion. Reshaping of American society was not the intention of most policymakers in the government and business, maximising war effort was the prime and only objective[7].

Persuading housewives to take up jobs at the war industrial production factories was not an easy task. There was a major public opinion against the idea of housewives working in factories. Soon enough, the government started initiating campaigns to encourage women to join the war material production scene. In April 1942, the War Manpower Commission (WMC) was formed to look into the matter of war labour issues in the military, industrial, and civilian sectors[8]. The government’s focus was on the policies to sell the war as a step towards labour mobilisation[9]. The War Manpower Commission and the Office of War Information (OWI) arranged several promotional campaigns to persuade women to take up jobs in the war production factories[10]. The campaign bodies got to work and began their persuasion through different means of propaganda, visual propaganda being the most effective one. There was an immense support from The War Advertising Council (WAC) for government campaigns and all kinds of advertisers, encouraging them to continue war-related advertising as they believed that this was the most effective way “to sell products or win goodwill during the war.”[11]

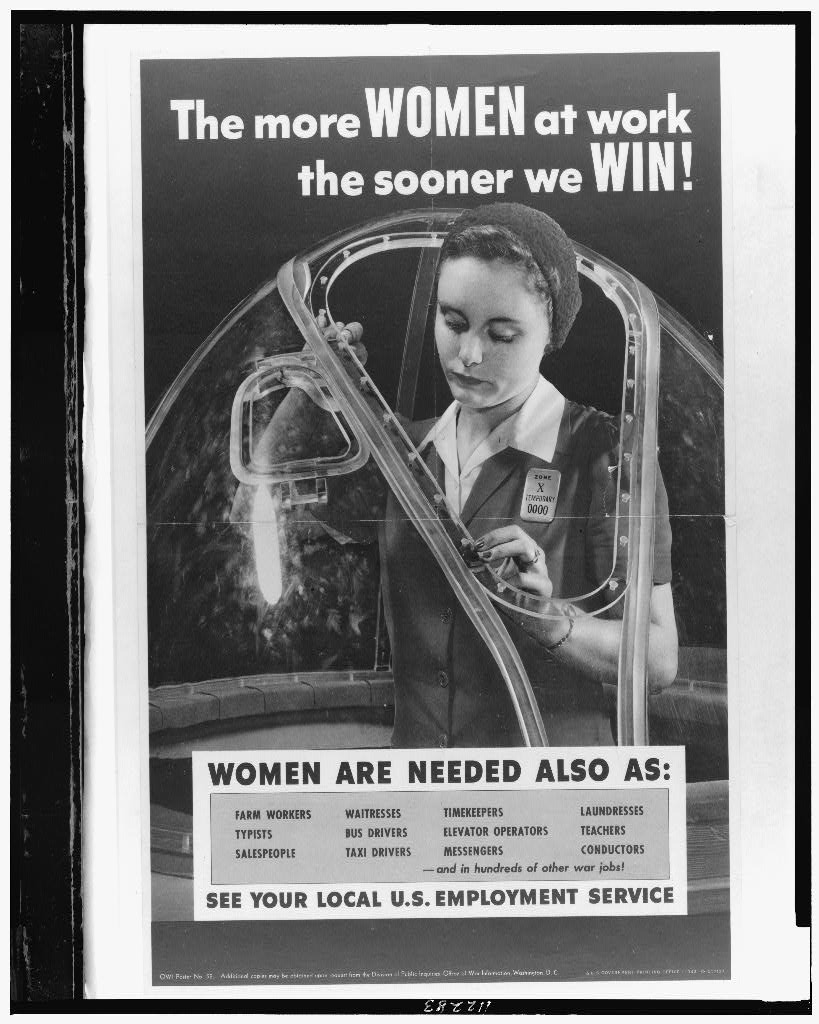

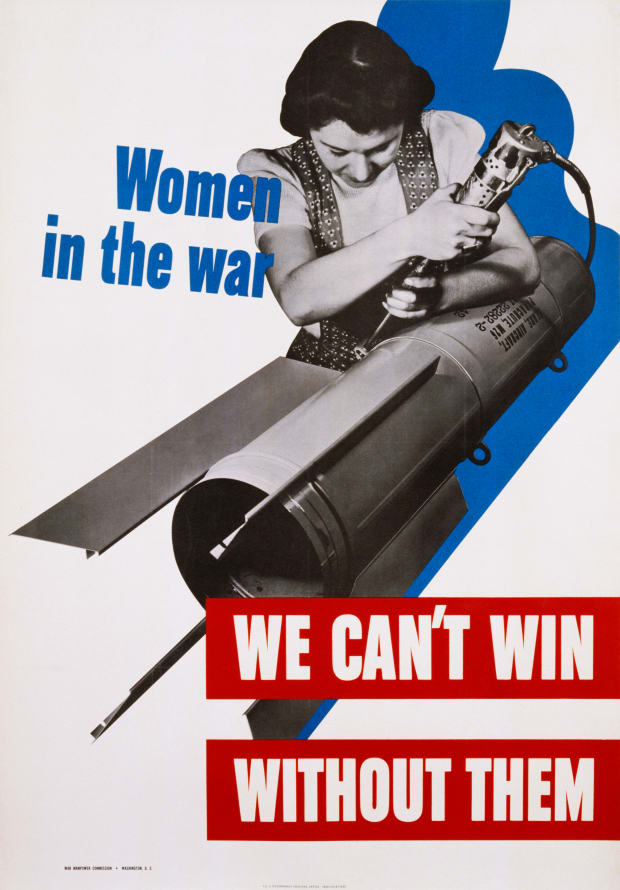

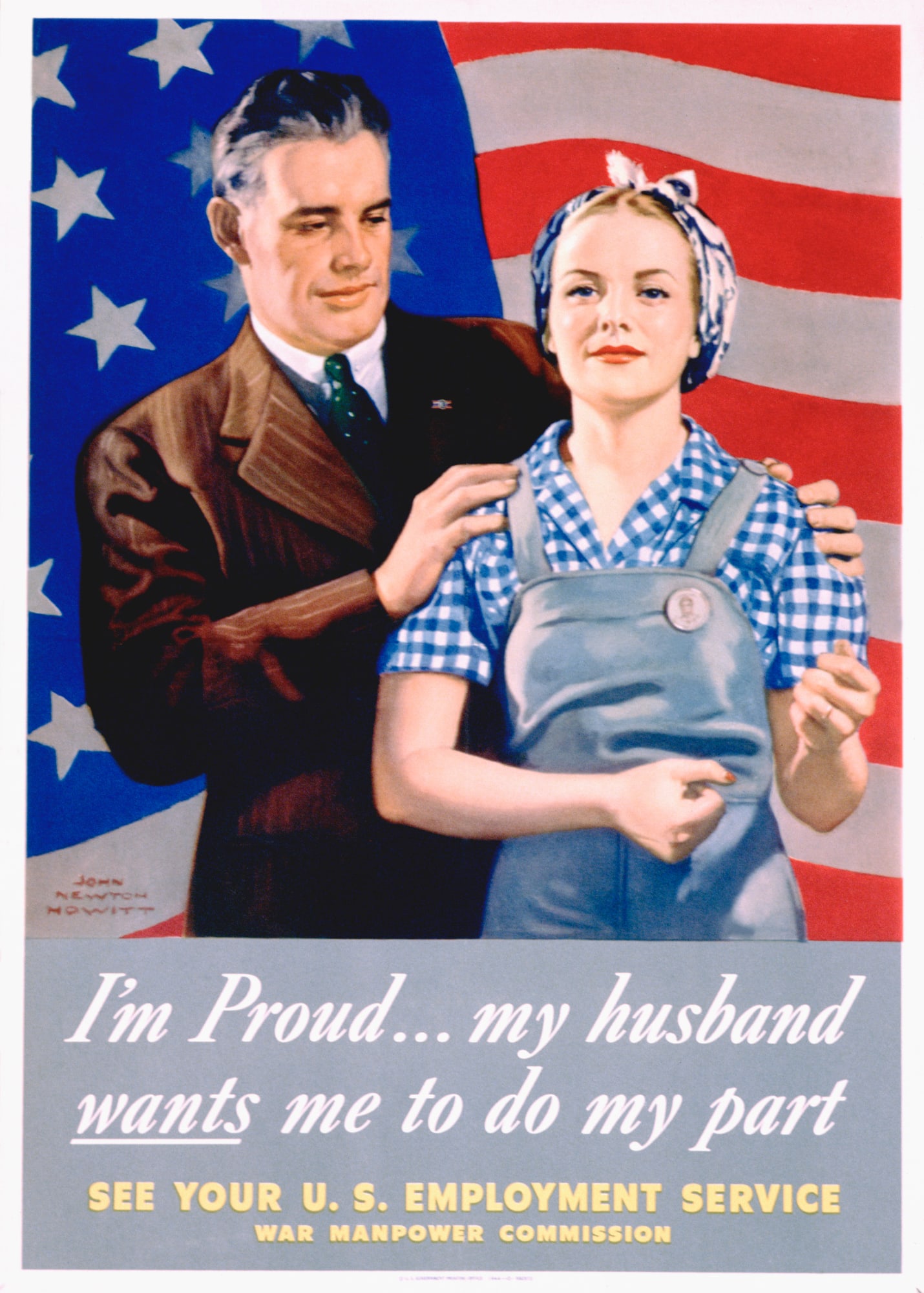

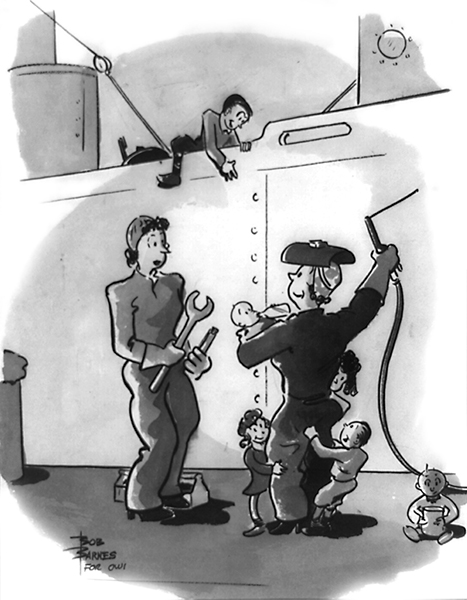

The country was swamped with posters and magazine articles all aimed at the housewives and young women of the United States of America. The campaigns were successful in glamorising war production work that it was as “pleasant and easy as running a sewing machine, or using a vacuum cleaner”[12] and showing that women could have the best of both worlds, being the docile home-maker while being the efficient and patriotic American woman. Attempts in persuading women to consider wartime work included, short films such as Glamour Girls of 1943 were featured in theatres all over the country, magazines featured women workers on the front covers of the issue and campaigns run with catchy and thematic slogans such as “The More Women at Work, the Sooner We’ll Win” (see Figure 1), “Every idle machine may mean a dead soldier”, to mention a few. Several posters headed with slogans such as, “Do the Job He Left Behind” (see Figure 2), “Women in the War- We Can’t Win Without Them”, “Soldiers Without Guns”, all depicting noble, patriotic women war workers were popular[13]. It may be noted that these slogans and themes varied in terms of creating an alarmist call out instigating a sense of fear. Appeals specifically directed to husbands were done by the campaigns. One such example has been cited by Leila J. Rupp, “It may be a bit of a shock, but YOU are going to have to help!”[14]

Figure 3 shows us a timeless feminist icon imagery, Rosie the Riveter. The woman in the poster is flexing her arm showing her physical strength, with her makeup on and uniform, she was ready to fill in the shoes of the men at the factories. The image of the woman in the poster eludes fierceness, boldness, patriotism and physical strength, which at the time were the qualities the government was looking for the women of America to put into action. She has neatly bobbed hair tied up in a bandana, in a war job uniform. The usage of the words in the poster such as “We” is interesting as it calls on to the women emphasising on ‘woman power’. Initially designed by J. Howard Miller for the Westinghouse Electric Corporation, this icon caught on so well, that the Four Vagabonds wrote a song about Rosie rewriting history. Several other variations of Rosie were printed and circulated.

The poster depicted in Figure 4, seems to be aimed at the men in the community to urge them to send the women in their family to work. It shows a woman at work handling a war weapon. The writing on the poster points out that this war can not be won without the help of women in the production of war weaponry. Figure 5 below too is aimed at both the men and women of the society, especially the men to encourage women to do their part in the war effort as at that time there was reluctance seen among the men to send their wives or daughters to work since it did not exactly conform to a ‘feminine’ job.

In the above figures showing few of the many posters that were printed in order to persuade women to take up jobs in the war production units, it may be observed that the women portrayed in these posters are depicted as proud, noble, efficient and feminine at the same time. Women pictured in Figures 1,2 and 5 resemble Rosie the Riveter. These posters were aimed at housewives who held onto the ‘traditional womanly virtues’, and these posters assured them that by enlisting for wartime jobs they are doing a great service for their country and their family, by giving a hand in the production of war equipments and the notion that more the number of equipments are produced, quicker the war will be won and soon they will reunite with their families who are out fighting the war. The colours used in the above posters are quite brilliant, red, blue and white that constitutes the American flag. The clever usage of colours were not only seen in the type but the images of the posters as well, for instance the uniform of the women in posters is blue, their bandana is red and the white is incorporated either as the background or type or even in the attire of the person depicted in the poster. These subtle but effective considerations played a pivotal role in instigating a sense of patriotism and duty in the reader.

Women depicted in these adverts wore makeup as a badge of femininity while tending ‘masculine jobs’ and hence cosmetic products were being widely advertised at this time since according to surveys it was found that beauty products not only served its purpose of aestheticity but also it psychologically helped women to wear makeup as a badge of bravery and nobility as per the advertisers of Hold-Pin Bobs[15]. The posters also addressed the doubt the American women posed that if these jobs will make them less feminine. The wartime jobs were glorified or rather beautified through these strategically designed posters. One other aspect that one can think of is that these posters empowered women a certain way. It changed the way they saw themselves, and it changed forever when they started working or rather got the feel of freedom.

In Figure 6, one can observe women workers at the Glenn L. Martin Company welding aircraft parts in the 1940s at Offutt Air Force Base, Neb. The photograph resembles ‘Rosie the Riveter’ in several ways. The woman in the image is in a workers uniform, wearing a bandana and tending to a welding job. Though she is immersed in a job that requires quite the elbow grease, her appearance is not tainted. Just like Rosie, she is well-groomed. One may not know for sure if this image was used to show other women that factory jobs were as easy as ‘operating a sewing machine’ and that while they were busy with ‘masculine jobs’ their femininity is in no way affected.

Women’s magazines were the most sought means of communication and played a crucial role during both pre-war and post-war times. Before the government required women to join the war work, women’s magazine was a platform bombarded with advertisements, articles and information on product rationing, tips for frugal shopping, tips on parenting and beauty care[16]. Women’s magazine editors were instructed to focus the content towards supporting the war effort and to portray women accepting the wartime pressures and requirements in a noble and efficient way[17]. Magazines were not the only forms of media through which the government attempted to persuade. Radio channels began hosting sessions in favour of enlistment and films were featured all across the country which portrayed women getting to work for their country which ultimately did well for their families.

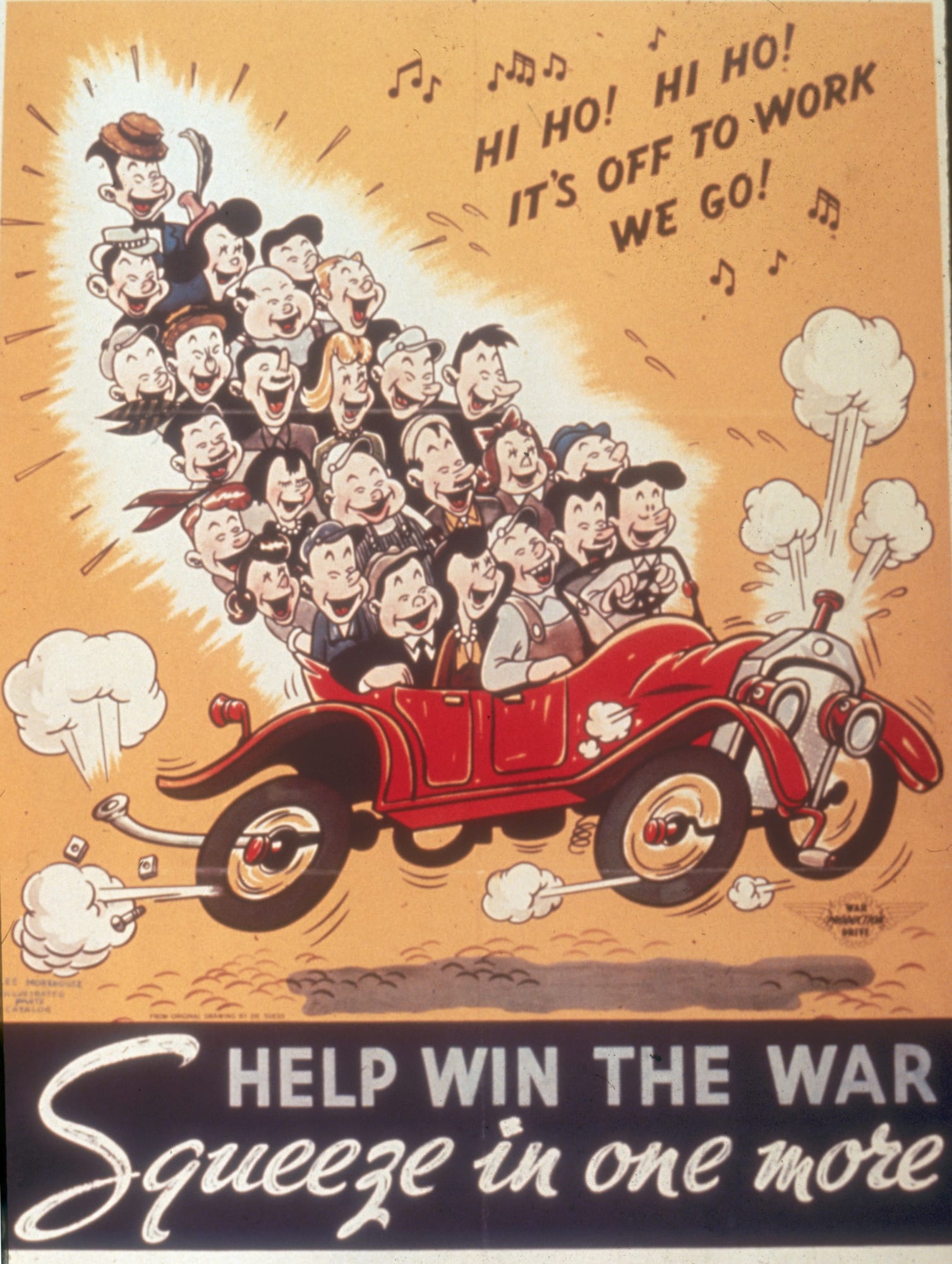

Although advertising through various means of mass communication played a pivotal role in persuading women to enlist for wartime jobs, one of the main reasons for women to join the workforce apart from patriotism was the financial incentives and support the jobs had offered[18]. All was not merry for the new factory workers. Women were in a difficult situation because they had to balance work and childcare which was tedious because of the demanding hours of their jobs. The government recognised the issues faced by the women, shortly the Lanham Act was passed which provided grants for childcare services. Eleanor Roosevelt played a vital role in creating the first government-sponsored child care centre, the Community Facilities Act[19]. Several factories had set up their own provision for workers’ children for childcare. Several reforms such as staggered working hours were brought about so as to help the working woman strike a balance between her family life and work life (See Figure 8). The campaigns were a huge success. By December 1941, about 12 million women were employed which increased to a whopping 16 million by early 1944. It was estimated that about 6 million women worked in the manufacturing sector of weapons[20]. Travel too was another issue for these women since many resided in the suburban areas and many did not have the luxury of owning a car, hence the government encouraged the workers to carpool (See below Figure 7).

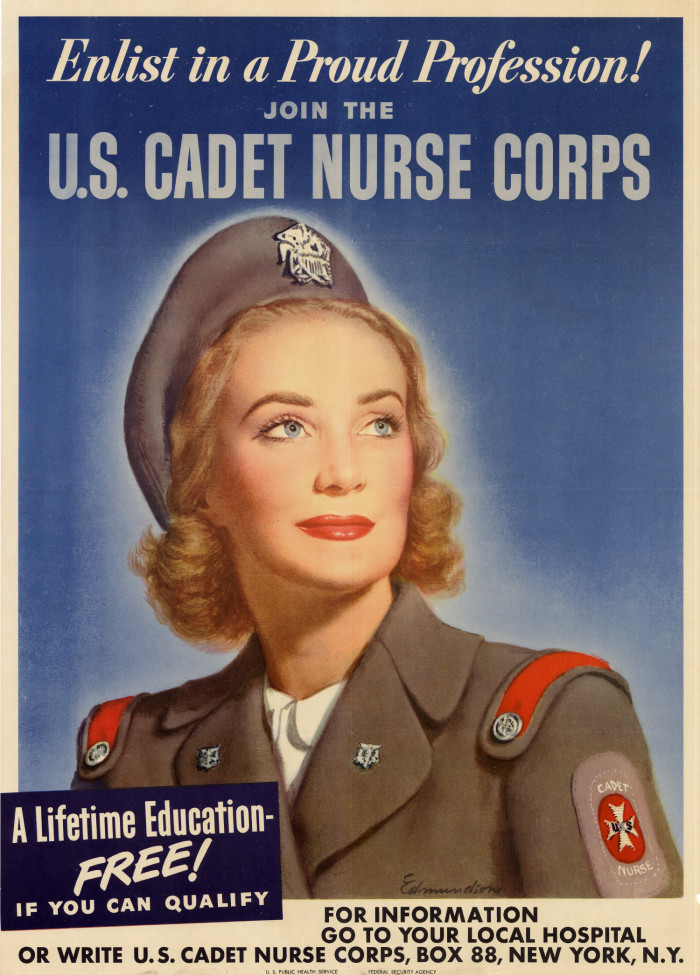

Though many women did not take up jobs at factories or the army, many did their part as volunteers. They sowed for the Red Cross, participated in civilian defence activities and even organised recreational services for members of the armed forces as well[21]. Women were also encouraged to join the Women's Land Army (WLA) as part of providing labour to farms to increase food production. A huge number of women volunteered as nurses or as members of home defence units as well. Several incentives were offered along with the job enlistment. In Figure 9 below, is a poster calling on to women to join the US Cadet Nurse Corps offering a lifetime free education if one qualifies.

Women did make their way to the military service of the United States as well. The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was formed in May 1942, and by July 1943 he WAC gained full military status. The Navy formed the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), the Coast Guard initiated the Semper Paratus (SPARS) and the Marines began recruiting women. By January 1943, all the military branches of the United States of America accepted women for service[22]. This temporary empowerment the women of America imbibed gave them a sense of individuality and purpose as they got the opportunity to make career choices, earn their own money and even dress differently.

The poster illustrated in Figure 10, is an example of a reminder for working women that once the war is over, they are expected to go back home to look after their families full time. This is an advertisement by Adel Precision Product Corp. in 1944, which was widely circulated in the magazines at the time. In the poster, one can see that a mother who is rushing off for work at the factory is stopped by her daughter who is eager to know when her mother will be staying at home with her. This kind of advertising was growing in number to tailor the minds of the women to return back to domesticity when the war ends. Little did they know that once a section of the society is empowered and discovers their capability and purpose, no amount of advertising or campaigning can make things go back to as they were before. America was about to witness a wave of reconstruction in their ideology of gender roles in the second half of the 20th century.

After the Second World War had ended, the very government that encouraged women to get out of their kitchens and pick up tools to work, started persuading women to go back to their kitchens since their service is no longer needed as the men have returned from war. Although women working was promoted as a temporary change in gender role, things could never go back to the same old conventions of a ‘woman’s role’ since women got to taste freedom and understood that they are capable of much more things rather than just domestic housework. As Emily Yellin writes, “But as was the norm in those days, any newfound independence or accomplishment was always tempered, if not curbed, by the idea that no matter what they did, women should maintain a feminine image doing it. Otherwise their gains, according to the prevailing notions of women’s roles, came at too high a cost to the values of American society.”[23] There was this emergence of a new woman, who defied the traditional norms and glass roof. The one who worked outside of their homes, who were financially independent. Emily Yellin also quotes Max Lerner who noted that the traditional image of a woman is being shattered. There is not much a difference in behaviour between a group of ladies and a group of men coming out of the factory. He adds on by saying that there is a version of a woman who is masculine and a total opposite of the ‘traditional feminine woman’. He even remarks about them by calling them ‘Amazons’[24].

Several women lost their jobs, and vacancies were made ready for the war veterans who would be returning. Susan Mathis quotes Carol Berkin and Mary Beth Norton from their work Women of America: A History, stating that:

The problem was to avoid massive unemployment after the war, and to government policy makers, unemployed was a male adjective… Eighty percent of… working women...tried to keep their jobs. Most were unsuccessful. Layoffs, demotion in rank and pay, outright firings, all eliminated women from their wartime positions.[25]

The self-confidence and esteem of the working women of America had soared if not they came to a realisation of it. Judy Barrett Litoff and David C. Smith have written a paper on the effects of World War II in the lives of women in the United States by examining private records such as wartime letters written by ‘American identified’ women. One particularly notable mention is the letter written by Edith Speert, who worked as a supervisor of a child care centre in Cleveland, Ohio. She writes to her husband about the immense sense of purpose and satisfaction she gets from her job. She writes, “I must admit I’m not exactly the same girl you left- I’m twice as independent as I used to be and to top it off, I sometimes think I’ve become as ‘hard as nails’- hardly anyone can evoke any sympathy from me.”[26] Yet another account that Emily Yellin writes about is of Naomi Craig who had worked at Federal Products in Providence, Rhode Island, making precision instruments for war production. Naomi Craig describes the issues faced by women who got the taste of ‘freedom’ has changed them and now having to go back to house work poses a state of unrest. The war employment gave women financial independence. She no longer had to ask her spouse for money. She could spend it at her will since it was her hard earned money. But now having to go back to ‘begging’ and having watched over for every little thing seemed to be creating a lot of tension. She says that women no longer knew how to ‘be wives’ anymore[27]. All of the aforementioned accounts gives us an understanding of the sense of freedom and self that the women of America had acquired through these wartime jobs.

“There is no example in which a class or group of people who have once succeeded in expanding the area of their lives is ever persuaded again to restrict it.” ~ Dorothy Thompson

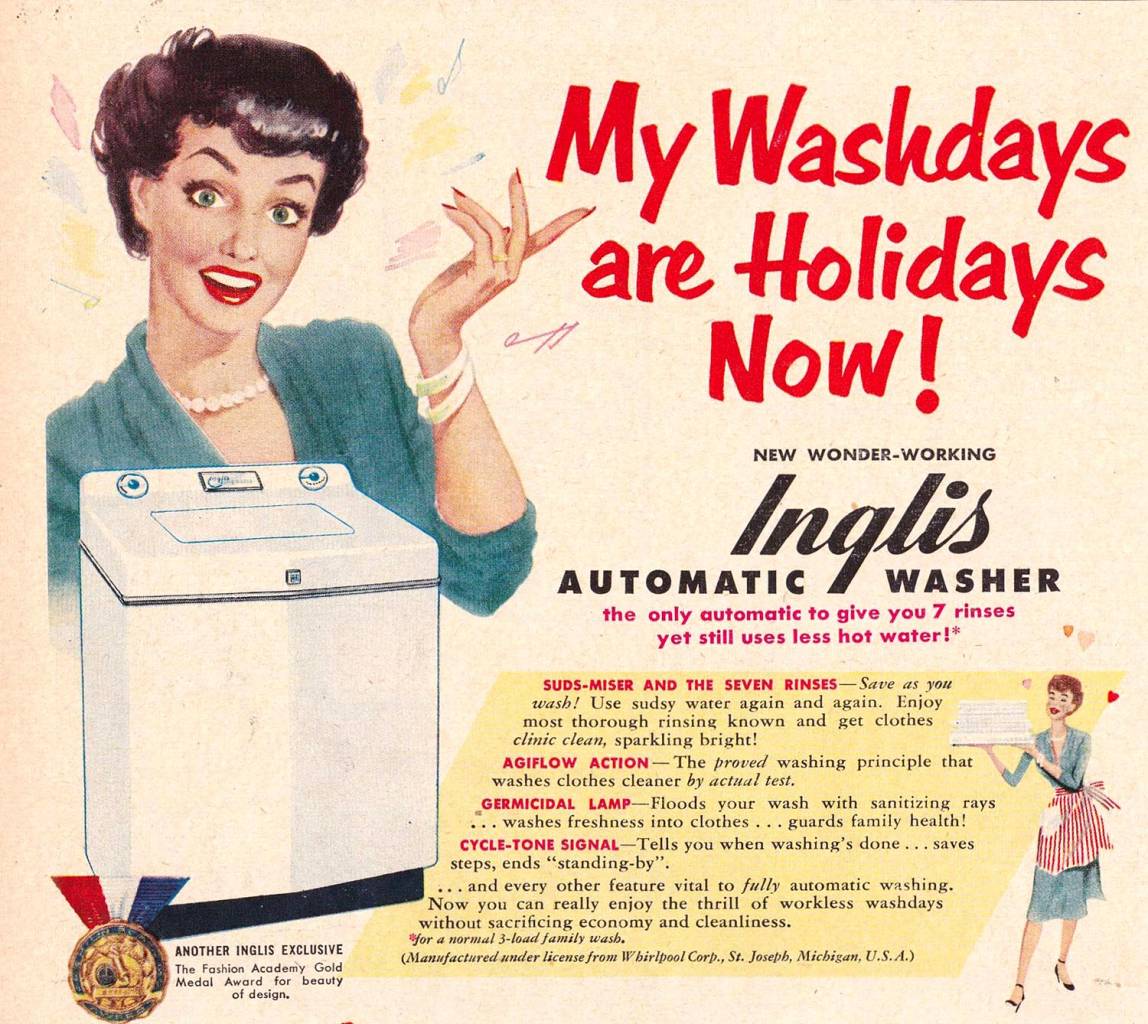

The government used the same means of visual propaganda to encourage women to take pride in giving up their wartime jobs and going back to ‘homemaking’. Magazines began picturing women tending to their families, decorating homes, and cooking. Ellen Lupton’s Mechanical Brides discusses the capitalisation of the conflict between a woman’s ‘domestic obligation’ and desires by some employers and unions in order to cement the ideal role of a woman and to discourage women from competing with men for wages[28]. Advertisements of the latest household technologies swarmed in magazines and other mass communication media. The intention of this advertising was dual. One, promotion of latest technology and two, the highly emphasised one, was to persuade women to take up the domestic homefront full time. These advertisements sent the message that with the advent of these new technologies, home making has never been so easy and it is guaranteed to give a woman more free time and more free time meant that she could give more time to her family once her domestic duties are done. These advertisements were pasted over the ambitions and dreams of many women, forcing them to go back to conforming to ‘traditional stereotypical gender roles’. Along with the duties of taking care of children, cooking and cleaning, women were now expected to be consumers. Angela Partington writes, “The consumption of new goods and services became part of the housewife’s expanded job-description.”[29]

A few examples of the aforementioned genre of advertisements are shown below. These advertisements not only targeted women as consumers but they portrayed homemaking as a ‘serious profession’ and certain designs of household technologies such as the decorator fridge gives a woman the liberty to choose what is best for her home attributing to the skill of homemaking (see Figure 12). Thus, “the consuming woman of the 1950s had the power, through purchasing, to change her image and, by doing so, possibly change her life as well.”[30]

Figure 11 is an advertisement by the Edison Electric Institute in 1966. The advertisement comprises a woman who has fallen in love with the machine that promises her more free time and easy cloth drying, while the boys in the family, her husband and children, watch their mother gazing at the machine. Figure 13 is an advertisement of Inglis Automatic Washer published in the 1950s that highlights the ease of operating the washer and now a woman who owns this machine has more leisure time on her hands. These modern technological systems depended on the presumption that women would stay at home and continue to do full time homemaking. However, there was a surge in the number of women who entered the labour force despite the comfort and leisure these household machines had offered as advertised[31].

Looking into the other means of mass media, Emily Westkaemper has done extensive study in the area of advertising targeting women and mentions Betty Friedan’s work, The Feminine Mystique, as it looked at the stark contrast in the fiction novels in women’s magazines, the portrayal of independent women with careers in 1939 and the articles published in 1949 which persuaded women to go back to homemaking[32]. Historical themes of an ‘ideal woman’, the docile, loving mother and wife, were prevalent in these magazines in an attempt to cement the significance of the stereotypical image of an American woman and promote ideals of domesticity.

Television programmes narrowed their focus on historical drama, showing the character and traits possessed by the traditional women which were abundant in such shows. Emily remarks that these historical references reassured that a woman’s interest in homemaking is biological and it was a tradition that once could take pride in[33]. Friedan states that American culture had quietly brushed the feminist histories under the carpet, by bombarding values of domesticity. It has to be mentioned that even films were made focusing on portraying the need for women to wear their ‘ideal suit’. One such noteworthy example is Calamity Jane which was released in 1953. The story revolves around Calamity Jane, or ‘The WildWest heroine’, who is tomboyish in her mannerisms and dressing. She is transformed into a ‘woman’ by Katie, who helps her redecorate her cabin and also helps her in dressing up as a ‘lady’. This scene is played as a musical where Calamity and Katie are singing and performing ‘A Woman’s touch’. The song itself stresses on the notion that a woman is not a lady unless she is in the right attire, grooms herself well and carries herself with poise and elegance, and that domesticity is central.

Ruth Schwartz writes that in the 1950s and the 1960s, women were put down by renowned writers, psychiatrists and even psychologists when they expressed their wish to pursue a career[34]. During that period, magazines rarely published anything related to a working woman and blamed them for the surge in juvenile cases, divorce cases and the increase in male impotence[35]. These technologies that were intended to keep women at home offering leisure time, were mere ‘catalysts’, in the words of Ruth Schwartz Cowan, for more women to join the workforce. Women realised that with the help of these new household technologies they could balance their work and house better than before. Though the Second World War brought about several vicissitudes, it paved the way for several civil rights movements in shattering the stereotypical dichotomy of gender roles in a typical American home. In the words of Dorothy Thompson, “There is no example in which a class or group of people who have once succeeded in expanding the area of their lives is ever persuaded again to restrict it.”[36] The rest is history.

[1] Deborah L Rotman, "Separate Spheres?: Beyond the Dichotomies of Domesticity." Current Anthropology 47, no. 4 (2006): 666-74. Accessed May 18, 2020. DOI:10.1086/506286.

[2] Leila J. Rupp, "Occupation: Housewife": The Image of Women in the United States" In Mobilizing Women for War: German and American Propaganda, 1939-1945, 51-73. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978.

[3] Leila J. Rupp, "Occupation: Housewife", 66.

[4] Leila J. Rupp, "Occupation: Housewife", 71.

[5] Emily Yellin, Chapter 2: Soldiers without Guns, Our Mothers' War: American Women at Home and at the Front During World War II, 39.

[6] Yellin, Soldiers without Guns, 39.

[7] Cynthia H. Enloe, "Was It "The Good War" for Women?" American Quarterly 37, no. 4 (1985): 627-31. Accessed May 17, 2020. DOI:10.2307/2712587.

[8] Yellin, Soldiers without Guns, 44.

[9] Leila J. Rupp "Mobilization and Propaganda Policies in Germany and the United States." In Mobilizing Women for War: German and American Propaganda, 1939-1945, 74-114. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978, 90.

[10], [11] Leila J. Rupp, "Mobilization and Propaganda in Germany and the United States", 93.

[12] "U.S. Government Campaign on Manpower", revised as of Dec. 5, 1942, RG 208, Box 166. Cited in Leila J. Rupp, "Mobilization and Propaganda in Germany and the United States", 96.

[13] Emily Yellin, Chapter 2: Soldiers without Guns, Our Mothers' War: American Women at Home and at the Front During World War II, 46.

[14] "U.S. Government OWI Womanpower Campaigns", RG 208, Box 156. Cited in Leila J. Rupp, "Mobilization and Propaganda in Germany and the United States", 97.

[15] P. D. Delano, Making up for war: sexuality and citizenship in wartime culture. Fem. Stud. 24, 33–68. (2000) DOI:10.2307/3178592 Cited in "From Empowerment to Domesticity: The Case of ... - Frontiers." Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2016.00016/full.

[16] Emily Yellin, Chapter 1: To Bring Him Home Safely, Our Mothers' War: American Women at Home and at the Front During World War II, 25.

[17] Yellin, To Bring Him Home Safely, 25.

[18] Yellin, Soldiers without Guns, 46.

[19] "American Women in World War II - History.com." 28 Feb. 2020, https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/american-women-in-world-war-ii-1. Accessed May 17. 2020.

[20] Mary Elizabeth Pidgeon. Changes in Women's Employment During the War. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, Women's Bureau, June 1944. Cited in "Propaganda to Mobilize Women for World War II." http://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/publications/se/5802/580210.html. Accessed May 17. 2020.

[21] Doris Weatherford. American Women in WWII. New York: Facts on File, 1990, 220. Cited in "Propaganda to Mobilize Women for World War II." http://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/publications/se/5802/580210.html. Accessed May 17. 2020.

[22] Doris Weatherford. American Women in WWII. New York: Facts on File, 1990, 19. Cited in "Propaganda to Mobilize Women for World War II."

[23], [24] Yellin, Soldiers without Guns, 54.

[25] Carol Berkin and Mary Beth Norton. Women of America: A History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1979, 279.

[26] Judy Barrett Litoff and David C. Smith. "U.S. Women on the Home Front in World War II." The Historian 57, no. 2 (1995), 354.

[27] Yellin, Soldiers without Guns, 69.

[28] Ellen Lupton, Mechanical brides: women and machines from home to office, 1993, New York: Cooper-Hewitt, National Museum of Design, Smithsonian Institution, 9.

[29] Judy Attfield and Pat Kirkham. A View from the Interior: Women and Design. Repr. With new material ed. London: Women's Press, 1995.

[30] Catalano, Christina (2002) "Shaping the American Woman: Feminism and Advertising in the 1950s," Constructing the Past: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 6, 50.

[31] Ruth Schwartz Cowan." More work for mother: The ironies of household technology from the open hearth to the microwave". New York: Basic Books, 1983, 202.

[32] Emily Westkaemper, "YOU'VE COME A LONG WAY, BABY": WOMEN'S HISTORY IN CONSUMER CULTURE FROM WORLD WAR II TO WOMEN'S LIBERATION" In Selling Women's History: Packaging Feminism in Twentieth-Century American Popular Culture, 165. NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY; LONDON: Rutgers University Press, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1j0ptj5.11.

[33] Emily Westkaemper, "YOU'VE COME A LONG WAY, BABY", 168.

[34], [35] Ruth Schwartz Cowan." More work for mother: The ironies of household technology from the open hearth to the microwave". New York: Basic Books, 1983, 203.

[36] Doris Weatherford. American Women in WWII. New York: Facts on File, 1990, 308. Cited in "Propaganda to Mobilize Women for World War II."