2021 / Visual & Critical Studies

Rachel Quigley

A Singular Story: Responses to the dominant iconographies of international aid in Ireland.

In our daily lives we are often confronted with images of suffering in far off places that many of us may never see in person...

If you’ve ever watched daytime TV the odds are you will have seen footage of a starving child while a booming voiceover asks for your help in the form of €2 per week, these images are on billboards, they’re in newspapers, they’re online and, if you grew up in Ireland you have probably dropped a coin into a Trócaire box at least once in your life. These images can stir up feelings up anger, sadness, guilt, pity and even nostalgia in some.

As someone who has worked in the charity sector, I have seen my fair share of these types of images and I realised that for much of the public, the images they see of the so-called developing world are primarily through the lens of the charitable organisations who work in these communities. Before beginning my research, I had some general ideas about the history of charity in Ireland, I knew that we had Christian missionaries who worked in Africa and parts of Asia before the formation of Ireland’s biggest foreign Aid charities like Trócaire and Concern and I knew that many Irish people take great pride in our foreign aid activities and see it as part of our unique Irish identity.

This video essay is a companion piece to a larger project which examines the imaging of international aid as shown through the lens of Irish organisations. From the African Missions to modern day NGOs, attention is given to how design practitioners, organisations and regulatory bodies have responded to and challenged the dominant iconographies of international aid.

"...there is a danger when only one singular, one dimensional, story is told."

At the mere mention of missions in Africa or Trócaire boxes you may already have conjured up several images. Perhaps a starving child, fields of decimated crops or a lone mother cradling a baby. Theorists like Kate Manzo have commented on NGO’s reliance on images of children particularly the “starving baby” images that have come to represent vulnerability to famine, natural disaster, and war. These visual tropes carry with them a long and complicated history. Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie has spoken about her experience of reading primarily British and American children’s novels during her adolescence noting that she had only a singular idea of what books could be about. Later when she studied in America, she compared her experience of being misunderstood by her white American roommate to her own pre-conceived notions of a young boy names Fide whom her wealthy, middle-class family had employed, and whose poverty she had been taught to pity. Acknowledging the single-story of Africa that has come from Western literature, citing the work of John Locke and Rudyard Kipling, she makes special mention of imagery attributed to Africa:

"If I had not grown up in Nigeria, and if all I knew about Africa were from popular images, I too would think that Africa was a place of beautiful landscapes, beautiful animals, and incomprehensible people, fighting senseless wars, dying of poverty and AIDS, unable to speak for themselves, and waiting to be saved, by a kind, white foreigner. I would see Africans in the same way that I, as a child, had seen Fide's family."

This type of imagery attributed to foreign Aid organisations is one of the most dominant and enduring depictions of Africa and by extension much of the Global South by the Global North. The enduring consequence of this singular narrative is that it “It robs people of dignity”.

Countries that comprise the Global South are often defined through their differences to the Global North. The splitting of the world into two opposing categories is a deliberate manoeuvre in which the West positions itself as superior. This split is something that theorist Stuart Hall has commented on many times: “The world is first divided, symbolically, into good-bad, us-them, attractive-disgusting, civilized-uncivilized, the West-the Rest.” ,a society which seeks to assert its self-proclaimed dignity cannot do so without first declaring who is undignified.

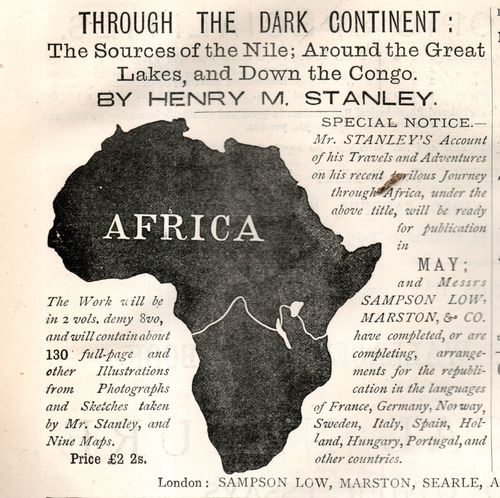

Historically speaking, Africa has been labelled “The Dark Continent” particularly by European and American writers. In his satirical piece How to Write About Africa, Kenyan author, and journalist Binyavanga Wainaina lists the “characters” that must be included to fit this view of Africa and he too references the types of visuals which were typically circulated by NGOs, those of “The Starving African, who wanders the refugee camp nearly naked, and waits for the benevolence of the West. Her children have flies on their eyelids and pot bellies, and her breasts are flat and empty.”

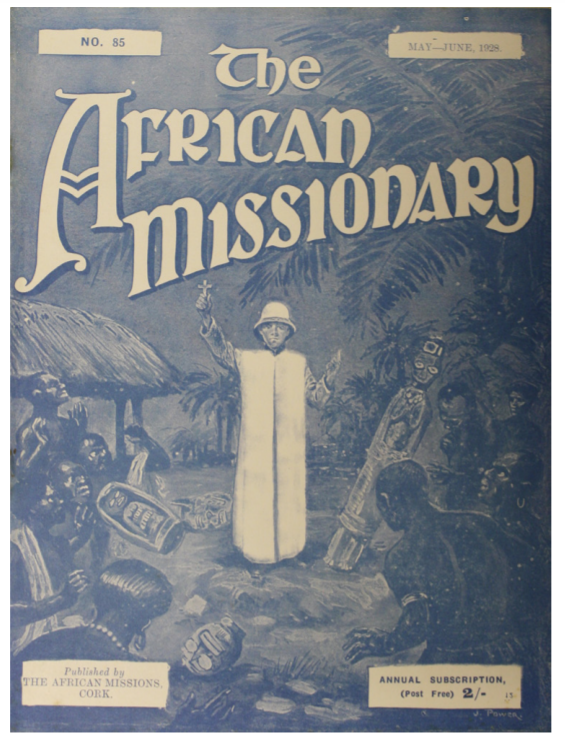

While Ireland has long and complicated history of being under British rule the framing of Africa as a continent which needs the paternalistic guidance of a Western nation was none-the-less a dominant mode of representation despite arguments that may be made about the shared colonial histories of Ireland and many African nations. Missionary magazines, which were incredibly popular reading for much of the twentieth century in Ireland, were rife with the kind of “characters” listed in How to Write About Africa. Unfortunately, as Dennis Linehan notes, “the Irish were adept at trafficking in images, narratives and rationales made up of Africanist tropes and imagery established in colonialist depictions of the continent.”.

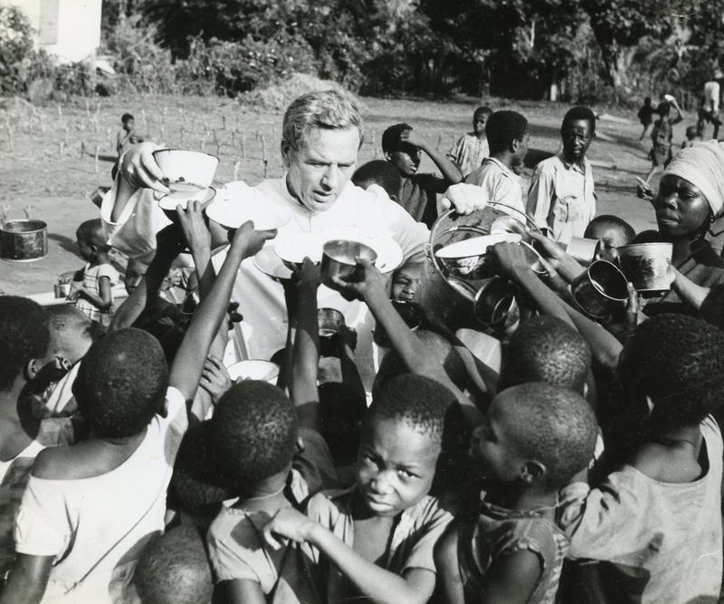

Covers like The African Missionary (1928) centre the white missionary as the Christlike saviour, clothed in white, surrounded by half-clothed natives presumably practicing a pagan religion, the antithesis of Christianity. The African characters on the cover echo Wainaina’s characters, the “Guerrillas”, “Timeless”, “Primordial” and “Tribal” Africans who live in jungles, clothed “in Masai or Zulu or Dogon dress “.

Many families had a member in the missions and images of Africa shown in missionary magazines were often the only representations of Africa that were seen by many in Ireland.

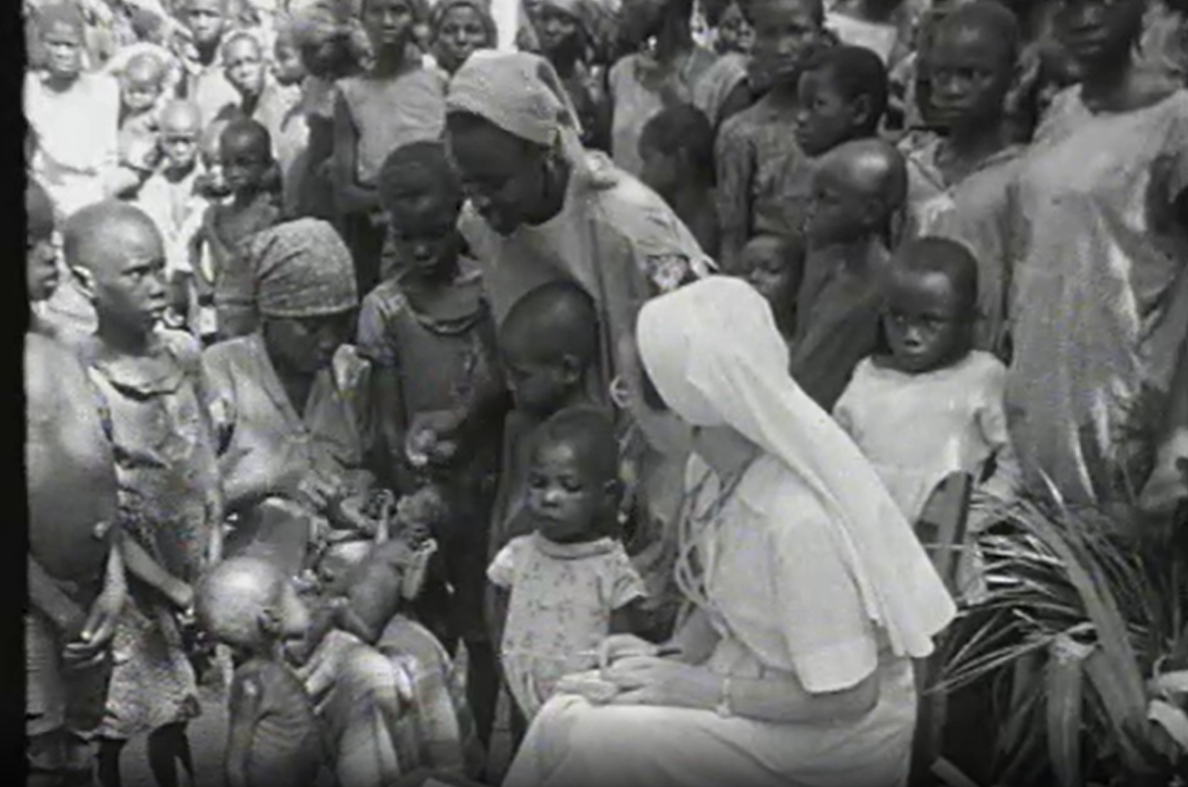

In the decades that followed Irish missionaries in Africa, who worked in what was referred to as “Ireland’s spiritual empire” would become heavily engaged in aid work particularly at the outbreak of the Nigerian-Biafran war in 1967. In Ireland, Children collected pennies for the “black babies” pictured on collection boxes displayed in churches, schools, and shops. Many families had a member in the missions and images of Africa shown in missionary magazines were often the only representations of Africa that were seen by many in Ireland. But as Radharc co-founder Joe Dunn remarked in his book No Tigers in Africa “Everybody knew television would be coming and coming soon” and, if ever there was an example of The Catholic Church taking full advantage of modern technology it is the documentary series Radharc.

Radharc brought images of poverty and famine in developing nations into the living rooms of ordinary Irish people and highlighted the role of the Holy Ghost missionaries as well as Holy Rosary nuns, doctors and volunteers who distributed aid in Night Flight to Uli. With documentary films like Night Flight to Uli, Radharc, and by extension the Catholic Church had a great deal of control over how the Biafran famine and the Biafran people were represented, and, in this representation, members of the clergy and other white volunteers were the heroes.

So dominant are some of these tropes and modes of representation that they have endured over the decades in visual culture and linger today and it is these singular narratives of Africa and by extension the Global South that beg to be challenged. The writers that I have cited, Wainaina and Adichie challenge these representations in their writing and contemporary Western media occasionally attempts to challenge these tropes too in films like Black Panther (2018).

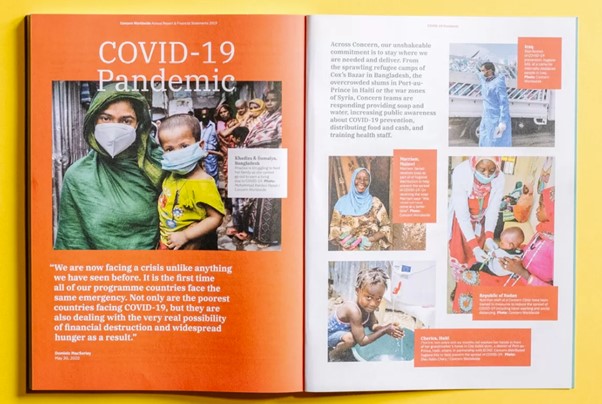

Irish NGOs like Concern (who can trace their founding back to Ireland’s missionary and aid activity in Biafra in the 1960’s) and organisations that followed, like Trócaire, have over the decades attempted to challenge these tropes as they become less acceptable and increasingly outdated. Guided by new regulations, codes and a desire to represent the people who benefit from their programmes with dignity the visuals employed by charities have changed over the decades.

Looking at the modern-day production of charity material it became clear, when speaking to practitioners like Red Dog’s Alessandra Ravida and Charlie O’Neil of Persuasion Republic, that the idea of representation with a dignity important to their practice in. An example of a structure in place which seeks to represent with dignity are Concern’s Global Brand Guidelines which were created by Red Dog for Concern’s use. It is these guidelines which informed the “visual language”, as designer Alessandra puts it, that she used to design Concern’s 2019 Annual Report. The Brand Refresh Guidelines as they pertain to the use of imagery follow the principles of the Dóchas Code of Conduct on Images and Messages. This code discourages any changes made to an image that would appear to exaggerate vulnerability, reinforce stereotypes, enhance the subject’s poverty, or otherwise remove important context through cropping, changing colours, extreme angles or editing.

Tone of voice guidelines dictates what photographs would potentially be selected and for what purpose and the importance of showing context, representing realities, and supporting imagery with copy is consistent across the board; images may provide an emotional punch, but they should also inspire action and “should always portray the dignity of their subjects”. The guidelines recommend different colour palettes for each situation to convey the tone via a visual language of colour declaring which palette is most appropriate and ensuring that colour and photography are never just ornamental, they are used with great purpose and always with context.

...when it comes to foreign aid it is important to cast a critical eye on both past and present representations and ask ourselves how we can respect the dignity of those we choose to represent?

Theorist Stuart Hall Wrote extensively about the various ways in which the “racialized regime of representation” could be challenged and one such method was the substitution of negative images for positive images. The goal of this approach is to invert binaries and expand the range of representation which can challenge reductive stereotypes.

This approach is often used by organisations and designers looking to challenge stereotypes. Alessandra remarked that with any image “there is more than just the blue scarf” , the image needs to be impactful in other ways too. When she looks through the image bank, she sees the captions and reads peoples stories, to achieve a design balance that respects the dignity of those who Concern helps and which creates a compelling case study, as she put it the photo “doesn't have to be a beautiful photo. It has to be impactful”. As Adichie and Wainaina would attest to, there is a danger when only one singular, one dimensional, story is told.

While we can acknowledge that a lot of good work was done when it comes to foreign aid it is important to cast a critical eye on both past and present representations and ask ourselves how we can respect the dignity of those we choose to represent? Creating a balance between truth and dignity is the challenge that practitioners and NGOs face. In documents like annual reports, but, across the board in corporate mailouts, fundraising materials and emergency appeals, standards and modes of representation have changed over the years and designers and organisations are mindful of the challenges ahead.